The recent appearance of Ebola in the United States has given rise to claims concerns at multiple levels for hospitals and other healthcare providers. The first U.S. case of Ebola came after a traveler from West Africa reportedly arrived without symptoms and sought care in a Dallas emergency department, only to be released home. When symptoms arose, he soon returned to that same hospital, was diagnosed with Ebola, and was treated but succumbed to his disease.

At its core, Ebola is a public health matter with significant similarities to other infectious public health events of the past. However, from a claims perspective, public health claims involve primary and secondary exposures for hospitals like the one at the center of current U.S. Ebola developments.

Primary exposure

Let’s look at the timeline for the patient who traveled from Africa to Dallas. He was infected in Africa and, therefore, the hospital is not responsible for that infection. Next, the issue of liability regarding the primary patient is one of a delay in diagnosis and the potential that his care was too late to be effective as a result of that delay. Recent publicity has cited the lack of timely diagnosis and care in the hospital. Based on known evidence, it seems likely that negligence exists. However, since the current Ebola strain is classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) as having a 70% mortality rate, and assuming a local jurisdictional causation standard of “more likely than not,” it seems reasonable to conclude that the primary patient was more likely than not going to survive.

Press articles report the family contends the patient was denied the therapy used with success on other Ebola-infected patients moved from West Africa to the U.S. for care. Those patients were given an untested anti-viral treatment and lived. News accounts report that anti-viral supply has been exhausted. If it develops that the Dallas hospital had this or other therapies available that were not used, the causation defense is jeopardized.

Secondary exposures

The major exposure in an infectious public health claim: one patient may become many. Those patients may be in a position to claim their infections were the direct result of healthcare negligence (or public health failure).

The secondary exposures thus far who have contracted the virus – two nurses who provided care for the primary patient – are hospital employees. It seems likely “exclusive remedy” under the Labor Code applies, and that a tort remedy is not available from the hospital. It remains to be determined if the involved physicians who did not make the diagnosis on the first emergency department visit have a non-employment exposure to the infected nurses.

The list of secondary exposures is long. There are the family members of the primary patient, others that he and his family and friends came into contact with prior to his diagnosis (estimated at 80, none of whom are reported as having symptoms thus far despite reaching the 21 day measure), the two infected nurses, both of whom spent at least a couple of weeks out in public prior to their diagnosis, including a commercial flight by one nurse.

It is easy to see that secondary infections may grow rapidly, causing health facilities to be busy with both infected patients and others who are frightened that they are infected.

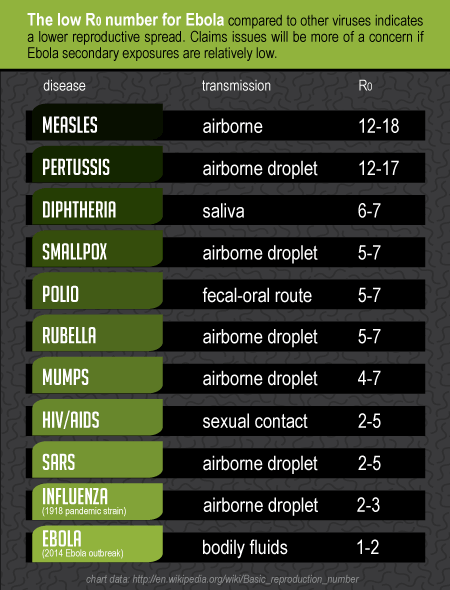

The measure of communication in viral infections is Ro, the basic reproduction number. This can be thought of as the number of cases one case generates on average over the course of its infectious period, in an otherwise uninfected population. The Ro for Ebola in the United States is presently 2. Any value greater than 1 means that viral spread has occurred and, in the absence of other data or developments, is likely to continue. A list of Ro for a variety of viruses is below.

At this writing, it seems public confidence in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), perhaps public health broadly, and certainly the Dallas hospital at the epicenter, is rapidly waning. Ro is only one aspect. The low Ro for Ebola seems encouraging compared to the vastly higher Ro for measles or pertussis – but for two factors: the lethality of Ebola given the (current) lack of effective therapy and the new and dynamic outbreak. Note that the century-ago Spanish flu had an Ro 2-3, and yet killed 50 million to 100 million worldwide.

The claims issues with secondary exposures will mainly be a concern if the Ebola secondary exposures are relatively low. If, for example, a worst case scenario occurs with a broader exposure, it seems likely that the claims system will lack the funding necessary to handle the claims. And we are already seeing that hospitals linked to Ebola complications are losing other patients. Should an Ebola outbreak reach numbers sufficient to threaten the infrastructure, Federal government relief is likely.

The most important thing this event has shown us is the need for preparedness and education of healthcare operations. We work every day helping our clients prepare for such events. I would be happy to answer your questions or hear your thoughts on where you see our readiness in the U.S. stands today for a major epidemic.

Jerry Frick, Director, Professional Liability Claims